Home

Memoirs of a Gamer

Movies I watched

Guidebook

Links

Home

Memoirs of a Gamer

Movies I watched

Guidebook

Links

the Lobdegg's Comprehensive Guidebook to DOS Programming

Chapter 2 - Video

Section 2: Early Graphics

(CGA and Hercules)

Introduction

A long time ago in a world very very near, IBM made a computer with no graphics standards as it was intended for businesses. Back then the average American business would go to printers for graphics, rather than computers. The relationships were already there so that wasn't what computers were for. BUT! What if computers had graphical capabilities with their data calculation capabilities? It wouldn't need much, black and white would be fine, right? Maybe add a splash of color just to highlight a pie chart or interlaced bar graphs. Memory was still super expensive so we want the lowest cost solution to punch up reports.

This meant that unlike video game console of the 80s which used special graphics processors that would work with tile maps and sprites, the IBM PC would get a card that focused on bitmaps. Basically just a massive grid of pixels which could be drawn to randomly. Need a bar graph? Simple, just plot it mathematically! Pie chart? Use most of the same code as the bar graph!

Yes, this was slower than what consoles were doing, but then no one in the business world was looking to create real time moving pictures. They wanted still images to augment reports. Thus we get the pragmatic foundations of PC graphics:

Initialization

Like most video modes covered by BIOS, initialization is as simple as calling int 0x10 with the correct video mode ID.Hercules Monochrome Graphics

CGA 4 Color Mode

CGA Monochrome Graphics

CGA 16 Color Graphics Hack

The only way to get 16 color graphics mode out of the limited CGA memory map is to piggy back off of the text mode driver. So first we set the video mode to CGA's 16 color text mode, then make each character 1 scanline tall and tell the video card that we want 100 rows of text. The thing is, we're still printing text, so what will happen on the hardware is it will read the character value then the attribute value and print the first scanline of the character before moving on. Normally CGA characters are several scanlines tall, and only after drawing all scanlines for the current row of characters does the card move on to the next row of text, but now that happens every single scanline.

Setting 160x100 16 color hack

| Assembly | Borland Turbo C++ / Open Watcom 16bit |

Open Watcom 32bit |

mov ax, 3

int 0x10

mov dx, 0x3D8

mov al, 1

out dx, al

sub dl, 4

mov ax, 0x7F04

out dx, ax

mov ax, 0x6406

out dx, ax

mov ax, 0x7007

out dx, ax

mov ax, 0x109

out dx, ax

add dl, 4

mov al, 9

out dx, al |

union REGS regs; regs.x.ax = 3; int86(0x10, ®s, ®s); outportb(0x3D8,1); outport(0x3D4,0x7F04); outport(0x3D4,0x6406); outport(0x3D4,0x7007); outport(0x3D4,0x0109); outportb(0x3D8,9); |

union REGS regs; regs.x.ax = 3; int386(0x10, ®s, ®s); outportb(0x3D8,1); outport(0x3D4,0x7F04); outport(0x3D4,0x6406); outport(0x3D4,0x7007); outport(0x3D4,0x0109); outportb(0x3D8,9); |

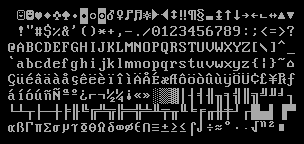

Since we're still technically printing text, we have to remember that colors are specified at every odd address in vram and there's a 'background' and a 'foreground' color for every byte of attribute data. Also, by default we should assume that every character has been set to an empty space character. This means only our background colors will shine through, so don't forget to print an appropriate character for every byte the card will try to draw. Something from the Code Page 437 extended glyphs should work nicely, like say 0xDD or 0xDE (the second to last row in the table below over towards the right hand side).

Of course, for full 16 colors per 'pixel', we'll need to deactivate that pesky blinking flag in text mode. That stops the pixels flashing if we set the 'background' color to anything 8 to 15.

Disable the blinking flag

| Assembly | Borland Turbo C++ / Open Watcom 16bit |

Open Watcom 32bit |

mov dx, 0x3DA

in al, dx

mov al, 0x30

mov dl, 0xC0

out dx, al

inc dx

in al, dx

and al, 0xF7

dec dx

out dx, al |

char t; inportb(0x3DA); outportb(0x3C0,0x30); t = inportb(0x3C1); outportb(0x3C0,t&0xF7); |

char t; inportb(0x3DA); outportb(0x3C0,0x30); t = inportb(0x3C1); outportb(0x3C0,t&0xF7); |